The Africa AI Council was endorsed at the inaugural Global AI Summit on Africa, which was co-hosted by the Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution (C4IR) and the Ministry of Information Communication Technology and Innovation in Kigali, Rwanda at the beginning of April 2025. The Council was initiated by Smart Africa, an alliance of 40 African countries and a wide range of partners committed to accelerating sustainable socioeconomic development on the continent. The alliance also has roots in Kigali, namely the 2013 Transform Africa Summit, which aimed to strengthen connectivity across the continent and stimulate private-public partnerships to drive African digital futures. The 2013 Summit culminated in seven African countries—Rwanda, Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, Mali, Gabon, and Burkina Faso—adopting the Smart Africa Manifesto. Other regional actors, such as C4IR, Qhala, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, have now partnered with Smart Africa to develop the Council’s strategy and provide its secretariat services.

So far, little has been published about the Council. Its agenda is not yet publicly defined, while artificial intelligence’s (AI) impacts on the region are increasingly tangible. Smart Africa’s Director General and Chief Executive Officer Lacina Koné said the Council’s overarching purpose would be to enable the continent to “leverage AI to transform its economies, industries and societies.” Its general focus will be on assisting African states to develop the emerging AI industry and establish Africa as an AI-driven global economy. It aims to play a unifying role in coordinating AI strategies and harnessing AI for sustainable development. With an emphasis on catalyzing innovation, the Council will likely refrain from taking regulation-heavy positions.

The beneficial potential of AI has brought significant hope to the future of sustainable development and economic growth in Africa. Koné explained the stakes of not investing in AI as “a definite economic setback and an ever-increasing technological dependence on the United States and China.” Broadly, AI is estimated to contribute $2.9 trillion to the African economy by 2030. However, investment in AI should lead not only toward advancing its adoption but also its safety—one that safeguards African peoples and borders. The downsides of AI include large-scale economic and societal impacts across the continent, which require timely understanding and mitigation.

This brief addresses the neglected yet crucial need for strengthening Africa’s AI safety capacity and outlines the potential role of the upcoming Africa AI Council in building it. The notion of capacity encompasses a variety of factors, such as skilled AI researchers, evidence on local AI impacts, evaluation platforms and methodologies or red-teaming efforts, among others. Finding the right balance between innovation and risk mitigation is a global challenge. In Africa, however, additional region-specific hurdles and policy dilemmas make this balance especially difficult for policymakers. The proposed recommendations aim to equip the Council with a regional agenda for building sovereign AI safety and security capacity and, therefore, positioning Africa in global AI governance as a contributor and collaborator.

The International AI Safety Report (2025), which was advised by representatives from Rwanda, Nigeria, and Kenya among others, documents the current capabilities and related risks posed by AI systems. The report focuses on malicious use risks (e.g., manipulation of public opinion, biological attacks), risks from malfunctions (e.g., bias, loss of control), and systemic risks (e.g., labor market risks, global research, and development divide). It states that the future of general-purpose AI is uncertain and there are currently no mitigation techniques that can fully resolve the already existing harms. To secure safety and benefits from this transformative technology, the report calls on researchers and policymakers to systematically identify the potential risks that come with advanced AI and to take informed action to mitigate them.

Africa is not immune to the societal risks of advanced AI, and some of these risks have already begun to materialize. For example, large language models (LLMs) have been documented to systematically perform better in English than in African languages. This issue directly translates into the models’ tendency to generate more false claims in African languages, which can spread disinformation and increase African users’ mistrust toward AI tools. What’s more, jailbreaks to access harmful responses are also more likely in low-resource languages, and OpenAI’s GPT-4 has been recorded to provide advice on committing terrorism when prompted in Zulu.

While AI bias, as a system-level risk, seems to have received more attention from African leaders compared to other risks, it is not the only safety concern that needs urgent attention and action. The impacts of highly capable AI on the continent could amount to large-scale setbacks, such as unparalleled manipulation, more damaging armed conflicts, or significant economic hardship. For example, incidents such as that of AI avatars spreading disinformation in Burkina Faso pose questions about the potential threats to the 2025 elections in Africa. Advanced AI systems could unleash serious national security threats and cause large-scale human devastation—or even human extinction—long before their promised benefits are realized. Therefore, developing AI models requires international oversight that ensures global-level safety. African leaders should take a more anticipatory approach to harm mitigation, develop grounded safety frameworks, and establish sufficient AI safety capacity to protect their citizens.

AI safety doesn’t yet have a universal definition. Broadly, it refers to the prevention and mitigation of harm posed by AI systems. Some AI safety approaches include aligning the systems with societal values or setting up technical robustness measures to ensure a system’s integrity in the face of adversarial conditions, such as data poisoning. At its core, AI safety is intrinsically about protecting human rights and ensuring that innovation leads to widely beneficial scenarios.

However, because African voices are currently significantly excluded from global AI safety discussions, African communities are excluded from robust and contextualized guardrails that both control the future of AI systems and address today’s costs of AI development. African leaders must actively step into global AI safety discussions and expand regional capacity to ensure their communities’ local knowledge systems, values, and expertise are not only represented but also consulted to inform international AI governance. Relying solely on foreign AI strategies could prolong Africa’s vulnerabilities. The forthcoming Africa AI Council has an opportunity to move beyond generic AI safety language and unify the region on the concrete risks posed to its communities.

AI security is an increasingly dominant narrative that links AI safety and national defense issues. It emphasizes protecting AI systems from wrongful and harmful deployment, misuse, and attacks. Some risks include AI-enabled threats to critical national infrastructure, military attacks, terrorism, or cyberattacks. AI security threats are unevenly distributed and may be especially harmful to those who are least prepared to deal with them. AI systems may act as a force multiplier for criminal activities, and geopolitical competitive pressures may lead the AI-leading countries to deprioritize implementing or upgrading safeguards. In this context, protecting its own cultures, people, and social order may be one of Africa’s most important policy issues in the coming decade. Yet, for many African countries, AI safety and security remain background issues, far behind the more urgent policy decisions or strategies on deploying AI for economic growth. With its unifying mission, the Africa AI Council could develop a clearer statement of what AI security means for African countries, coordinate building regional AI safety and security capacity, and provide safeguards for all member states regardless of their AI development stage. National and regional AI security are not mutually exclusive, and the Council could provide an effective bridge between them.

AI sovereignty may refer to several things, such as control over the AI development process, data sovereignty, consent for AI adoption, and the more negative effects of AI nationalism. Here, AI sovereignty is used to recognize that AI technologies have unavoidable and significant impacts on a nation’s key elements: economy, security, and society. As a response, the Council’s leaders should build a more self-reliant expert capacity to mitigate the negative AI impacts while magnifying the positive ones. AI is a deeply strategic issue, and building independent national or regional capacity must go hand-in-hand with international cooperation. AI sovereignty is not a call for the Council to abandon its multistakeholder approach to governance, but a call to articulate a clear regional position on AI safety and security—one that can be voiced in global forums and support more balanced, collaborative partnerships.

AI safety, security, and sovereignty are deeply interconnected: Effective AI security requires comprehensive AI safety frameworks that are responsive to local contexts. As such, this brief recommends building a sovereign AI safety and security capacity to reduce overreliance on foreign expertise. The Africa AI Council has an opportunity to strengthen regional and strategic self-sufficiency that prioritizes safe and beneficial AI for African communities. In this context, sovereignty would involve understanding and addressing Africa-specific AI risks through context-relevant risk assessments and evaluations, while also safeguarding African societies from AI harms through regulation or binding frameworks, among others. A sovereign capacity would allow for joining international collaborations from a position of agency, rather than just an affected stakeholder, and promoting sovereignty to advance societal well-being, not authoritarian tendencies. The framing of building sovereign AI safety and security capacity is not intended to downplay the universal nature of AI risks. Instead, it aims to point out the specific need for expanding regional expertise on how to address and mitigate these risks as their impact on Africa may be disproportionately more severe.

Harnessing AI opportunities is inseparable from ensuring that current usage of AI tools is aligned with African values, responsive to African contexts, and protected from large-scale, detrimental misuse. The implementation of a rigorous AI safety agenda (e.g., the development of context-relevant impact and risk assessment frameworks) across Africa by the Africa AI Council would strengthen national and regional security, enable sustainable innovation, and help secure beneficial outcomes as AI technologies continue to evolve and deploy throughout the continent.

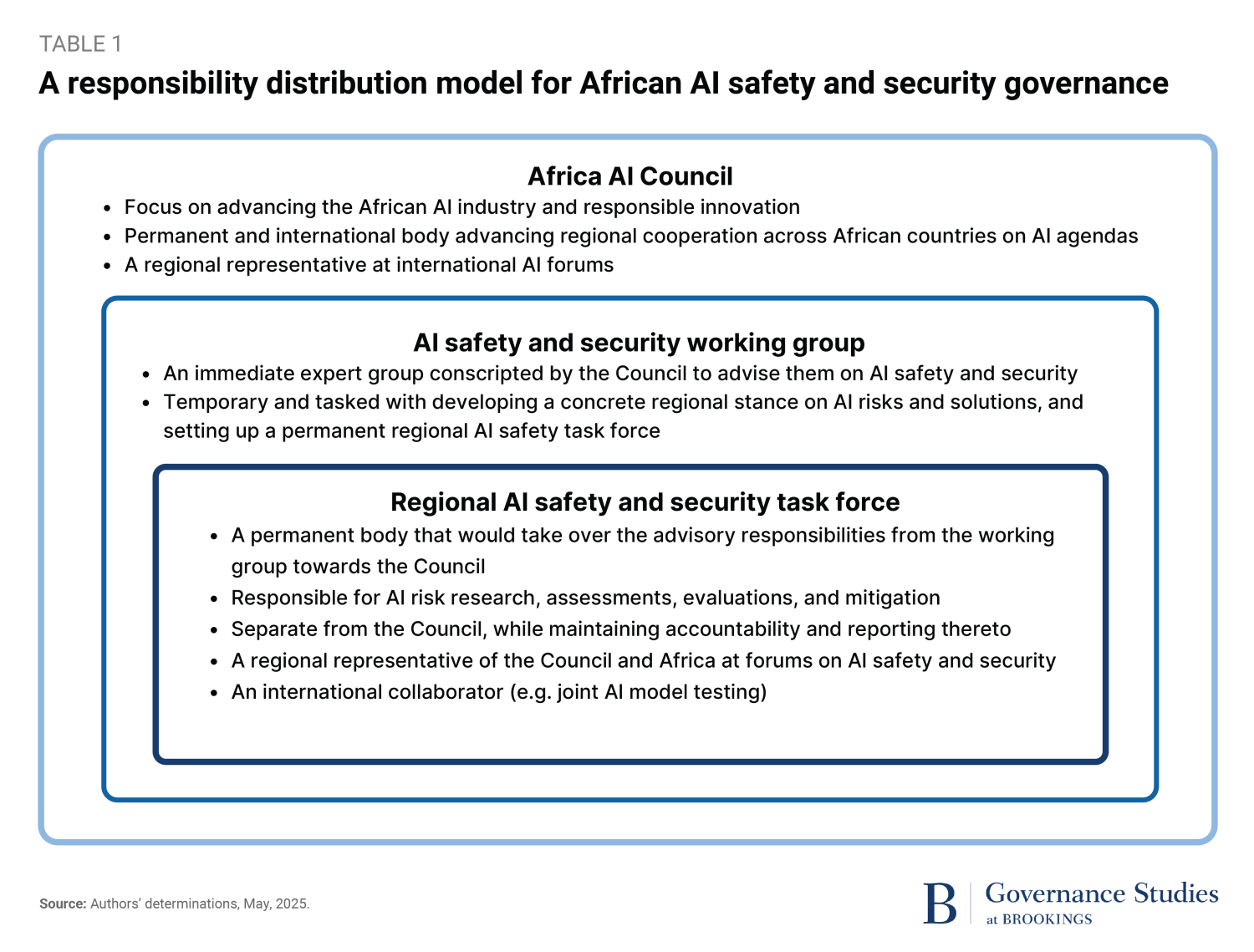

Given the large scale of the outlined challenges, it appears difficult for individual African countries to respond on their own and with the necessary immediacy. Therefore, we recommend a more regional approach facilitated by the Africa AI Council, which is also summarized in Table 1:

1. Convene an AI safety and security expert working group to develop a unified regional stance on AI safety and security in Africa

The Africa AI Council should convene an expert AI safety and security working group to develop a unified regional stance on AI risks and solutions and provide advice to the Council on AI safety and security strategies. This could both help guide national AI policy development and strengthen Africa’s voice in global forums. The initial working group can be immediately convened from existing African AI safety experts. It should be hosted at the Council yet have enough independence to collaborate with other stakeholders from across Africa in building a broader AI safety and security ecosystem.

The working group can act as the Council’s representative at international AI governance forums. For example, Africa’s exclusion from world-shaping discussions at the International Network of AI Safety Institutes represents a critical gap. Active participation in international AI safety and security discussions remains essential for accessing crucial risk information that will not be voluntarily shared otherwise. Without representation in these forums, African countries risk missing vital intelligence sharing that directly contributes to risk reduction across the continent. The Africa AI Council should prioritize low-cost yet high-reward engagement with international bodies to ensure the continent’s interests and unique contexts are considered in global AI governance frameworks.

2. Prescribe the creation of a regional and permanent AI safety and security task force

Recent recommendations outline building national AI governance over periods of 12 months or more—even up to 24 months and beyond. These timelines depict the lack of capacities across many African countries to act on safety and security sooner. However, given the unprecedented speed of AI capabilities’ advancement, there is a real need for establishing African AI safety and security infrastructure. The Africa AI Council is uniquely positioned to prescribe the creation of a regional AI safety and security task force as a more resource-efficient solution that can act with greater urgency. This would be a group of experts with sociotechnical knowledge tasked with ensuring the deployed models meet their safety standards and that safe, contextually tuned AI tools drive beneficial innovation across the continent. With its sovereign capacity, the continent can engage with global AI development from a position of strength rather than vulnerability. Additionally, a regional approach establishes necessary guardrails against the effects of foreign AI competition playing out across African markets. By pooling expertise and resources, African nations can protect their collective interests, allowing time for individual national strategies to develop in parallel.

Some other key considerations for building African AI safety and security capacity through the permanent AI safety and security task force include: choice of a host institution(s), speed of establishment, level of autonomy, proximity to inform policies and regulations, and top talent recruitment. The Council should consider building on the work of the already existing hubs, such as the Action Lab Africa, the ILINA Program, or the Wits MIND Institute.

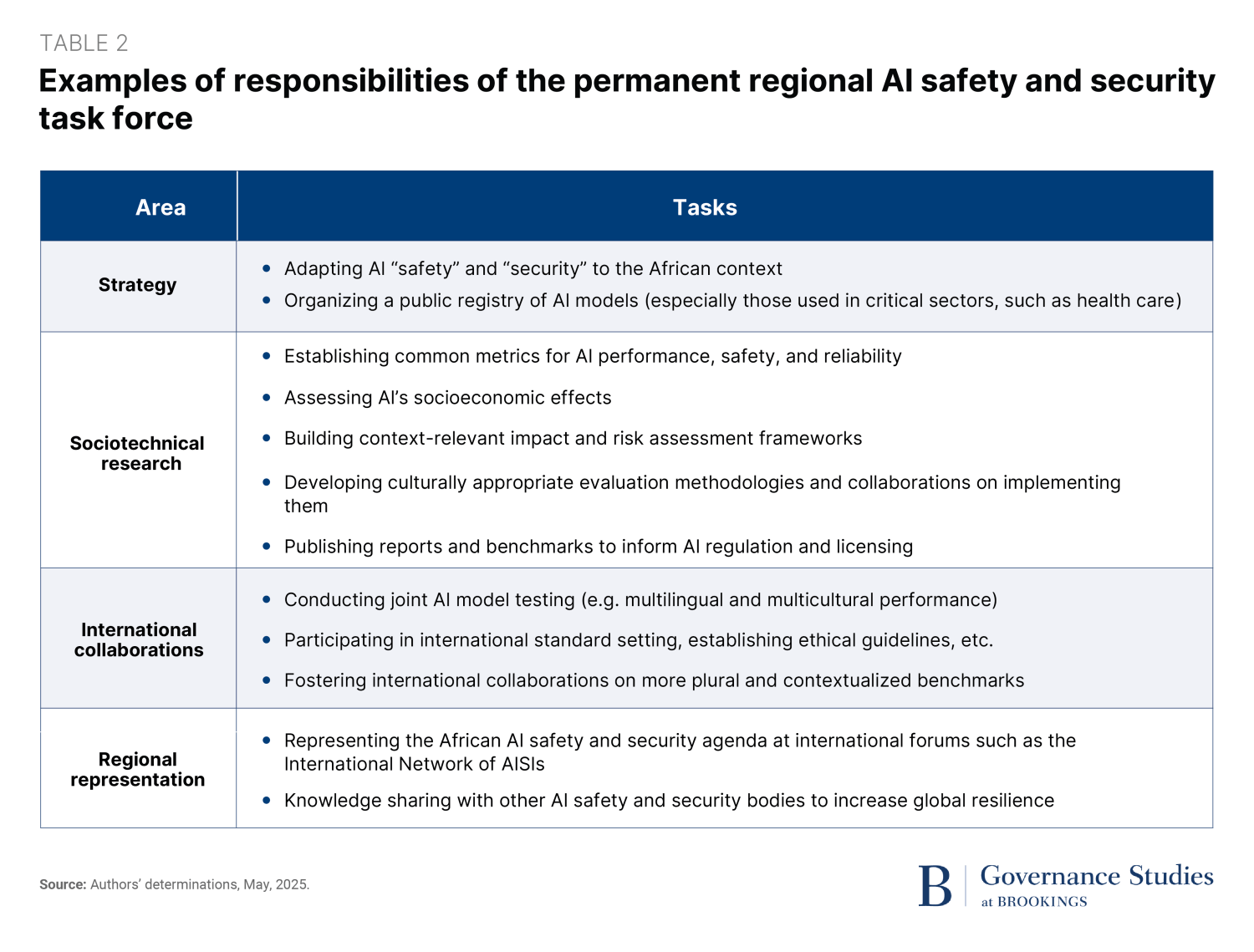

One of the key bottlenecks this task force can address is the lack of sufficient research available to the African governments that would allow them to ground their policies and regulatory objectives in a deep understanding of how AI-related risks may manifest in the specific contexts of their countries. Table 2 outlines some of the key responsibilities that the permanent regional AI safety and security task force could take on.

Strengthen AI safety and security capacity across Africa

The AI safety and security working group and task force can serve as the crucial connecting tissue between existing and future national AI safety and security units, ensuring coherent coordination and harmonization of safety and security strategies across borders. Together, the Council and the task force would actively support countries in developing their own national AI safety and security capabilities (e.g., risk frameworks, contextual AI performance benchmarks) while building on and engaging existing research institutions. As these national units mature, the regional task force would naturally evolve into a knowledge-sharing forum where best practices are exchanged and refined, allowing individual countries to conduct localized evaluations and research tailored to their specific contexts while ensuring cross-national exchange for regional security. This balanced approach preserves national sovereignty while maximizing the collective African capacity to address AI safety and security challenges that transcend borders.

Amid the growing evidence on the universal nature of large-scale AI risks, this brief calls for a more strategic approach to developing AI safety and security expertise in Africa by prioritizing regional capacity building. Sovereign research can equip African leaders to actively contribute to international AI governance and protect their citizens. The Africa AI Council has a unique opportunity to (1) develop a regional consensus on the gravity of AI risks and establish a forum to address them (i.e., the working group); (2) expand the sociotechnical capacity needed for conducting region-specific evaluations and research on AI impacts to inform local governments’ regulations and policies (i.e., the task force); and (3) increase Africa’s active participation in international forums tackling AI governance.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to extend special thanks for insightful comments to Stephanie Kasaon, Jonas Kgomo, Grace Chege, and Tomilayo Olatunde.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).